Most companies' supply chains constantly evolve in response to changing customer preferences and competitive pressures. That is why companies today seek to make their supply chains faster, cheaper, and capable of delivering a wider range of products while preserving high levels of quality. In many cases, manufacturers may execute these improvements by using new input materials in the production process, upgrading their technology or machines, changing the production process, or relocating manufacturing sites. An unintended consequence of these constant changes is an increase in unused fixed assets.

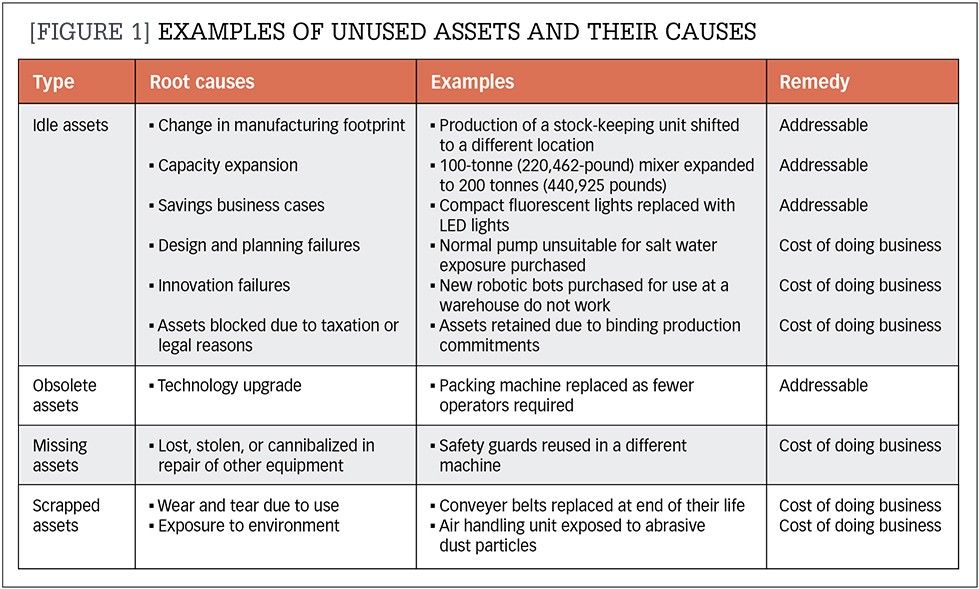

Unused assets (such as plants and machinery, lab or office equipment, and furniture and fixtures not in use) can be classified into four categories: idle, obsolete, missing, and scrap. Idle and obsolete assets may be either reusable or nonreusable. While idle assets incorporate recent technology, obsolete assets are technologically outdated. Both of those asset types may be redeployed; however, missing and scrapped assets can only be written off.

There are a number of root causes for unused-asset generation. Some of them are addressable and some are not, which means they must be accepted as a cost of doing business. Figure 1 provides some common examples of unused assets, their root causes, and whether or not they can be remedied.

In my experience, almost 90 percent of unused assets arise due to predetermined actions, such as changes in manufacturing footprint, capacity expansion, cost-cutting initiatives, or technology upgrades. All these factors can be addressed to reduce wastage. Other types of root causes—such as design and planning failures, innovation failures, taxation or legal issues, asset cannibalization, wear and tear of assets, or environmental exposure—are relatively difficult to control and make a comparatively small contribution to the total value of unused assets. 1

In financial accounting, an asset is a resource that is owned by a business and can be used to produce a future economic benefit. To ensure that users of financial statements, such as shareholders, creditors, suppliers, customers, and regulatory agencies, are presented a true and fair view of the company's financial position and performance, accounting standards require the value of assets to be correctly recorded in the balance sheet. If an asset present in the balance sheet is no longer useful, it must be written off. Asset write-offs can translate into a sizable impact on profitability and reduce a company's ability to benefit from its existing asset base.

The good news is that it's possible for a company to minimize these write-offs by putting in place certain internal processes. This article offers suggestions for reducing unused-asset write-offs through the following steps:

- Establish a digital database of all assets with details that will be useful when making future decisions about the disposition of unused assets;

- Address the root cause of each unused asset through process interventions;

- Utilize periodic physical verification as a tool to identify reusable assets; and

- Decide whether to store or sell each unused asset and follow the appropriate storage guidelines.

Executing these processes can help reduce asset write-offs significantly; some companies have even experienced reductions of up to 50 percent in these costs over the course of just one to two years. And there is more good news: These steps are applicable to any industry, and making those changes requires only a one-time effort.

The following sections explain the four steps in detail.

Step 1. Establish an asset database.

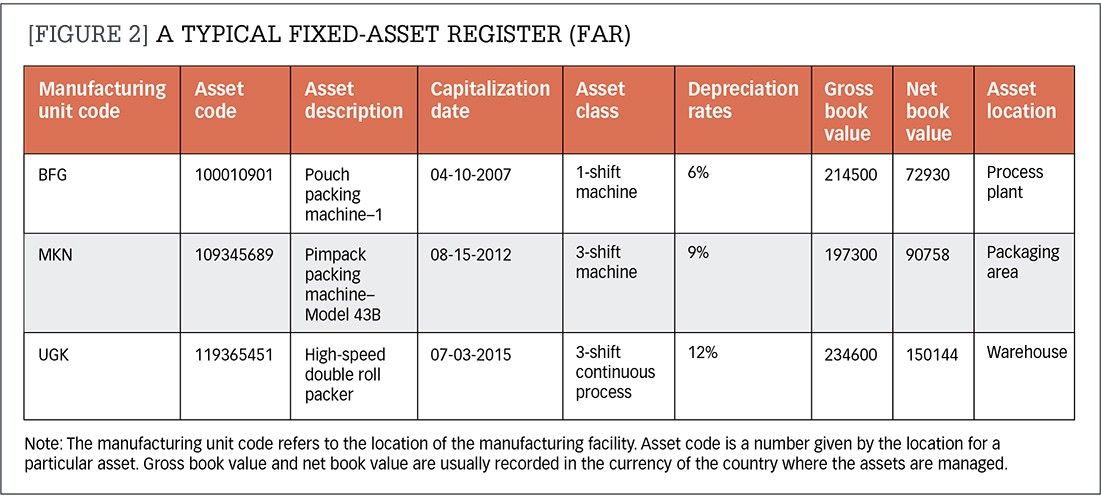

As organizations grow larger and more complex, a digital database of all assets becomes necessary for effective fixed-asset management and redeployment of unused assets. Such a database exists in most organizations in the form of a fixed-asset register (FAR), which is used to keep track of the book value of the assets and determine depreciation. But the information the FAR contains typically has limited relevance for making decisions about the redeployment of assets. See Figure 2 for an example of the kind of information typically included in a fixed-asset register.

One of the reasons why the FAR is not helpful for the redeployment of assets is that the quality of the data in the FAR in large organizations often suffers due to a lack of standardization. For instance, all assets in Figure 2 pertain to similar machines made by the same manufacturer, but it is hard to tell that from the FAR because each of the three locations have given them different asset descriptions and asset classes.

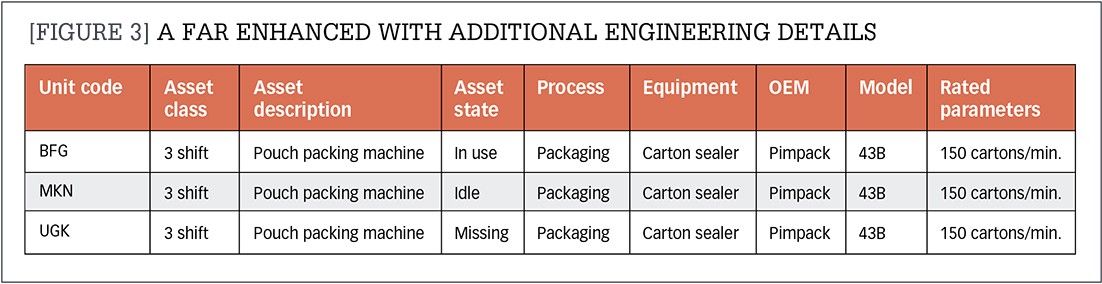

Companies can move toward better data standardization by creating a catalogue of all the types of assets used by a company. This may take the form of mapping an asset, such as a piece of equipment, to relevant processes. What constitutes the relevant processes depends on what information will be required to redeploy the asset in the future. For example, for a shoe manufacturer, the suitable processes to which an asset could be mapped might include material handling, stitching, shaping, coloring, and packaging. The catalogue could then drill down a few more levels to show the type of equipment used in each process. For example, equipment used for packaging may include filling, combining, wrapping, labelling, and sealing machines.

Each of these equipment classes would include products made by different original equipment manufacturers (OEMs). By including engineering details for each asset (such as the processes it is used for, the equipment class it belongs to, the OEM of the machine, and the machine parameters) in the FAR, the company can then assign machinery a process-equipment-OEM mapping field. The FAR we saw earlier would now have the following additional information, making it a valuable tool in facilitating asset redeployment (see Figure 3).

The process and equipment mapping fields in the FAR could help companies quickly identify unused assets that are suitable for redeployment in specific projects. In addition, by providing details about the state of the asset, the expanded FAR lets companies focus only on reusable assets and quickly write off missing and scrap assets.

The creation of a digital database and subsequent mapping for all existing assets is probably the most difficult, time-consuming, and expensive step in reducing asset wastage. However, it would involve a one-time effort to upgrade the details of all existing assets, and any additions to the FAR, thereafter, could be captured as part of the regular capitalization process. In my view, for companies with a large asset base, the benefits from an enhanced FAR in terms of asset redeployment, improved controls, and new insights are likely to greatly exceed the effort involved.

Step 2. Address each root cause.

Earlier in the article, we discussed how some root causes of unused assets are addressable and others are not. When it comes to mitigating write-offs from unused assets, the approach will differ based on whether they are due to root causes that are addressable or to root causes that are not addressable.

Process for addressable root causes: Most unused assets are generated from addressable root causes, such as decisions to change the organization's manufacturing footprint, expand its capacity, implement cost-saving initiatives, or upgrade machinery. These decisions are usually made after a rigorous capital expenditure (capex) evaluation to determine whether the investment meets the company's thresholds for return on investment (ROI). By adding a few steps to the business-case approval process, organizations can identify from the start whether these proposed projects will likely produce any unused assets or provide opportunities to redeploy currently idle equipment. Doing so can significantly reduce asset write-offs. The expanded business-case approval process is illustrated in Figure 4 and explained below.

1. Business case outline: Start with an outline of the business case as is normally done in capex proposals.

2. Write-off evaluation: The write-off evaluation is performed to identify the pipeline of unused assets. In this step, determine the assets that will likely be made redundant on execution of the business case. Take care to include second-order effects as well. For instance, if material that had been handled in bags will now be moved on a conveyor, include the crane used to move the bags to the factory warehouse and not just the forklift used inside the warehouse in the write-off evaluation.

3. Redeployment evaluation: The redeployment evaluation seeks to identify if any of the available unused assets could be deployed in a particular project. This can be done by comparing the available unused assets (suitable process and equipment filters can be applied in the expanded FAR) to the scope of the project to determine whether available assets could be used with minor modifications to the proposal.

4. Discount and trade-in evaluation: During this step, organizations need to examine whether the assets that will be made redundant can be resold to the equipment vendor for cash or accepted in exchange for a discount on the purchase of new equipment. Alternatively, some specialized vendors may be willing to identify other customers that might purchase these assets. This approach can be used effectively in negotiations when large purchases are planned at a minimal cost to the vendor.

5. Capex evaluation: In the final step, companies evaluate whether the business case or capex proposal meets their financial metric thresholds, for example, net present value (NPV), internal rate of return (IRR), and payback period. When doing so, they need to ensure that only incremental (or additional operating) cash inflows and outflows are factored into the evaluation. The write-off of an already owned asset should not be factored into the capex evaluation because the asset price is a sunk cost; that is, the cost has already been incurred and cannot be recovered.

If an existing unused asset or an asset purchased at a discounted price can be used in the project, then the cash outflows must be adjusted to reflect the lower capex spends. This will result in a better NPV and IRR for the proposal, making it a more attractive investment for the company.

If the proposal meets the return thresholds and is approved, then the details of the potential write-off of assets identified in the evaluation can be integrated with the project-execution timelines to create a pipeline view of available unused assets. By interlocking the potential write-off evaluation and internal reuse of assets with business-case initiation, a company will be able to move from addressing assets that are already unused to actively reducing the pipeline of unused assets.

Process for root cause that cannot be addressed: Root causes that lead to non-redeployable assets, such as those mapped to "cost of doing business" in Figure 1, can be mitigated by creating a feedback loop. While the asset may have to be finally written off, a company will still be able to reduce the frequency of similar instances happening in the future. The following are just a few examples of "cost of doing business" root causes and how to incorporate them into a feedback loop:

- Design and planning failures—These failures can be used to provide feedback on the real-world performance of the asset to the product designers (if the asset is made internally) or to the purchasers of the asset.

- Lost, stolen, or cannibalized for repairs—If a company has a high value of unused assets attributable to this root cause, it indicates a poor controls environment. To reduce these cases, analyze trends to identify whether assets at specific locations or of specific types are prone to being lost. These assets can then be tagged and tracked with radio frequency identification (RFID) tags. If an asset is to be cannibalized for repairs (that is, parts will be removed and used to repair other equipment), document this action with relevant approvals, as costs to purchase parts usually are lower than the value of a usable unused asset.

- Wear and tear on assets caused by usage—The financial impact of write-offs due to wear and tear on assets should be small. If not, it indicates a mismatch between financial depreciation rates (which are based on the average expected life for the asset class) and the physical depreciation rates of the machines. As a result, the manufacturing cost reported by the company, excluding write-offs, is understated. This problem may be addressed by increasing the financial depreciation rates for this asset class, if this is allowed by the regulations under which the company operates.

Step 3. Use physical verification.

In general, companies use a physical verification (PV) process to assure users of their financial statements that the assets mentioned on their balance sheet are physically present. In addition to its compliance function, PV can be a valuable tool for gathering data about whether available unused assets could be redeployed.

Physical verification may be conducted either by the location owner or by professionals dedicated to this activity. When multiple locations are involved, it may be beneficial to use a dedicated team to visit each location, undertake a PV, and gather data that would be useful for asset redeployment. Having a dedicated team also ensures that the company has consistent data collection practices.

The PV exercise should collect the following data:

- Physical condition of the asset: Whether the asset is in use, idle, obsolete, missing, or scrapped.

- State of the asset: Whether the asset is redeployable or not. Even otherwise-usable assets may not be redeployed in some cases. For instance, the cost of repairs may be prohibitive or the spare parts for the asset may no longer be available, resulting in a production loss if a breakdown were to occur on an active production line.

- Root cause of unused asset: The reason the asset is not in use. Examiners may use the root causes in Figure 1 to check whether the remedial measures outlined in Step 2 are effective.

- Additional data: For reusable assets, data that aids in redeployment. Examples include photographs of the asset, vendor drawings, and asset dimensions.

Data from the PV can be merged with the data generated during the expanded business case approval process and with the technical and financial details in the FAR. The PV helps identify the universe of unused assets, and the details that are generated during the business case approval process can show us which of these unused assets were anticipated. The difference between the two should arise largely on account of missing and scrap assets or due to "non-IRR" spends. Non-IRR spends are not undertaken to meet a financial objective, instead they are carried out for general health, well-being, safety, and environmental protection reasons. This data can then be used to determine whether assets are being missed in the write-off evaluation stage or whether unused assets are being generated due to other root causes, which can then be addressed.

In addition to the PV, it may be beneficial to have a software solution that can show a pipeline view of anticipated unused assets and available unused assets. This software could also automatically analyze the PV data and separate the anticipated unused assets from the unplanned unused assets (that is, those outside the business case). The data could also be used to develop an internal marketplace for unused assets that is interlinked with system-based capex-approval flows.

The PV frequency should be such that unused assets have a good chance of being redeployed before they wear out or are damaged by environmental exposure. Every one or two years is usually a suitable frequency for most organizations with large asset bases. Completing the exercise simultaneously across all locations will help leverage economies of scale in asset redeployment and sale.

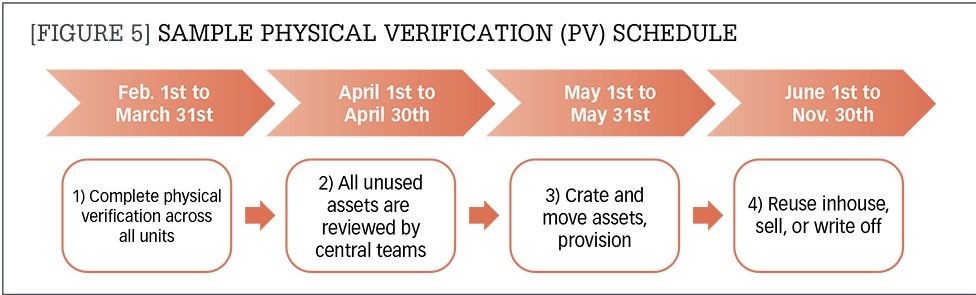

The PV schedule should comply with the regulations under which the entity operates and also allow enough time for asset redeployment. These schedules may therefore be designed for each of the countries in which the company operates. Figure 5 shows a typical schedule for a large company operating in one country that reviews all assets once every two years.

The schedule includes the following four stages:

Stage 1. Physical verifications are conducted simultaneously across all locations, and details of all unused assets are collected. It may be necessary to deploy multiple teams, all of whom should be trained on the data to be collected. The simultaneous PVs are required to ensure adequate scale for the next steps.

Stage 2. The inputs received are analyzed by central teams that then place all identified unused assets into one of the following categories: to be redeployed, to be stored, to be sold, or to be written off.

Stage 3. Based on that assessment, the following actions are taken: Nonreusable assets are written off and disposed of, and reusable assets are either moved to long-term storage or to the site of a capex project. Before reusable assets are crated and moved, the team should assess the value of the asset plus the cost of packing, movement, and storage, It is important to make sure that reusable assets that are to be stored are packed and stored according to engineering guidelines.

Stage 4. The financial impact of all the unused assets identified in the PV is recognized at the same time; that is, the asset value on the balance sheet is reduced and expenses are increased using a provision (an estimated amount set aside to cover an anticipated loss or liability). The financial impact recorded can be reversed if the asset is redeployed, or it can be rebranded as a write-off cost with no additional impact in the future.

PV is an effort-intensive and time-consuming process. The speed of a PV can be improved by using RFID or quick-response (QR)-coded tags instead of normal plain tags with just the asset code and asset description. The specialized tags can be made in various sizes with different variants allowing them to be used on flat, curved, rough, or smooth surfaces. The tags can be scanned with either a handheld scanner or a mobile phone. (The latter has the added benefit of being able to photograph the asset.) The exception to this would likely be very small equipment that may not be tagged, such as lab equipment and electronics. In that case, the tags may be applied at the location where these assets are usually kept. Also, the PV is easier if all assets are tagged at a standard spot on each piece of equipment. Adjacent to the asset name and technical specification plate affixed by the manufacturer is a good choice in most cases.

Step 4. Decide on storage vs. sale.

The data from the physical verification of assets and the data from the write-off evaluation can serve as tools to identify the supply of available unused assets. By interlocking those processes with the business case review process, companies can ensure that demand is created to utilize internally generated unused assets.

Reuse of assets should always be preferred to selling them, as doing so saves the capex cost of new equipment, which is much higher than the realization that would be possible from the sale of assets. In most cases reusing assets is a good bargain even after factoring in the benefits of purchasing new equipment. To maximize internal reuse, investigate the following questions:

- Can the asset be used in a different factory of the same business unit?

- Can the asset be moved to third parties that manufacture on behalf of the company?

- Is the asset usable in other countries where the company operates, and are the shipping costs justified?

When earmarking assets for internal use or sale, it's important to consider the probability of reuse. For example—although requirements will vary depending on the type of equipment and where and how it is stored—equipment with motors, in general, should be reused within six months of being packed, while static equipment can be stored for up to a year without deterioration. A list of the projected capex spends in the next six to 12 months is a useful aid for determining the potential of assets being reused. Based on that list, determine whether the types of projects being set up are likely to require the unused assets. If reuse of the assets does not seem likely in the next six to 12 months, then they may be put up for sale.

It's important to realize that selling unused assets is a process with long lead times. The general rule is that the more specialized the equipment, the sooner it should be put up for sale. On average, sales proceeds of 50 percent of an asset's book value can be considered a good realization. If the value of unused assets that cannot be reused within the company is significant, then it may be beneficial to hire a specialized firm to sell the unused assets through e-tendering auctions. In cases where the value of unused assets is low, the assets may be sold directly to other parties or to OEMs for cash or purchase discounts.

If the company decides to store the unused asset, it should make sure that proper storage guidelines are followed. It is not unusual for unused assets to be left without proper care in industrial settings, and this leads to rusting, loss of effectiveness, or breakdown of the assets, resulting in loss of value over time. Since there could be a significant time lag between asset availability and reuse opportunities, unused assets need to be stored in a manner that allows for their future reuse. This can be done by proper drying, maintenance, and storage in hard casings or protective wrap, depending on the nature of the asset. During packing, relevant details such as photographs of the asset in an assembled condition, operating and maintenance manuals, general arrangement drawings, and asset tag numbers are added to the asset package and to the digital database created in Step 1.

Packing of any idle or obsolete assets should be undertaken as soon as they are not in use. Packing assets is often an expensive activity, and it would be suitable to have a designated budget for crating, as this might be overlooked otherwise.

Keys to avoiding write-offs

Unused asset write-offs are a drag on profitability and at times a difficult issue to deal with. They frequently occur in companies where management is dealing with more serious problems, such as a declining industry or market share, excess capacity, or failed innovations, and they can end up taking management's focus away from what may well be a fight for survival. However, as this article has shown, any company, regardless of industry or business conditions, can use defined, rule-based processes to increase internal reuse of unused assets in routine business operations.

The key to success is to identify potential write-offs early on by monitoring business cases. Developing and making use of this pipeline of unused assets helps to avoid write-offs because it allows enough time to find reuse opportunities. Creating incentives for internal reuse of usable unused assets can further help to reduce write-offs. If the asset is not usable, then managers can educate the appropriate decision makers about mitigating actions that could address the root cause of the asset's unusable status. If there are no immediate plans for internal reuse of assets that are in good condition, they can decide whether the asset is to be stored or sold quickly to maximize realization from the sale. The digital database allows these steps to be put in place, while the physical verification process can ensure that the set-up is self-sustaining by acting as a feedback loop.

Notes:

1. The percentage of asset write-offs that are unavoidable may be higher in companies operating in rapidly changing industries or in new areas. In these cases, it is important to find the right balance between the various objectives of a company, such as launching new innovations or being the first to go to market in a new area, versus the risk of write-offs. Being too conservative restricts the growth opportunities of a firm, and it may be better to price the possibility of failure into the cost of products sold by the company rather than to try to avoid these write-offs.

ALAN has been helping to connect nonprofits with logistics resources since 2005. Here supplies are packed up for transport and distribution to Hurricane Maria survivors in 2017.Photo courtesy of ALAN

ALAN has been helping to connect nonprofits with logistics resources since 2005. Here supplies are packed up for transport and distribution to Hurricane Maria survivors in 2017.Photo courtesy of ALAN The nonprofit Unity in Disasters needed 30 pallets of food transported to Jackson, Miss., to help Hurricane Ida survivors in 2021. ALAN was on hand to coordinate a response.Photo courtesy of ALAN

The nonprofit Unity in Disasters needed 30 pallets of food transported to Jackson, Miss., to help Hurricane Ida survivors in 2021. ALAN was on hand to coordinate a response.Photo courtesy of ALAN